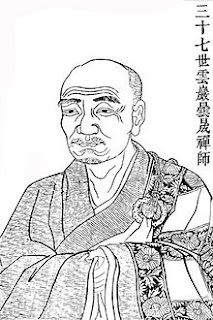

The Second Patriarch of Chinese

Zen was Huike. He was a Confucian scholar who sought a teacher to help him

resolve the concerns about life and death which weighed heavily on his mind. He

had visited many teachers, Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist.

He studied all three traditions and was well

versed not only in the Confucian classics but also in the doctrines of both the

Theravada and Mahayana schools of Buddhism.

Nothing, however, had brought him peace of mind.

In desperation he sought out the old

barbarian monk, Bodhidharma, who was said to have come from the land of the

Buddha.

When Huike presented himself at

Bodhidharma’s cave, the Indian monk suspected his visitor was another who came

seeking an intellectual explanation of Buddhist doctrine rather than the

experiential insight which comes from the practice of meditation. So for a long while he ignored Huike. The Confucian, however, remained patiently

outside the cave, waiting several days for Bodhidharma to acknowledge him.

One night, it began to

snow. The snow fell so heavily that by

morning, it was up to Huike’s knees.

Seeing this, Bodhidharma finally spoke to his visitor, asking, “What is

it you seek?”

“Your teaching,” Huike told him.

“The teaching of the Buddha is

subtle and difficult. Understanding can

only be acquired through strenuous effort, doing what is hard to do and

enduring what is hard to endure, continuing the practice for even countless

eons of time. How can a man of scant virtue and great vanity, such as yourself,

achieve it? Your puny efforts will only

end in failure.”

Huike drew his sword and cut off

his left arm, which he presented to Bodhidharma as evidence of the sincerity of

his intention.

“What you seek,” Bodhidharma

told him, “can’t be sought through another.”

“My mind isn’t at peace,” Huike

lamented. “Please, master, pacify it.”

“Very well. Bring your mind here, and I’ll pacify it.”

“I’ve sought it for these many

years, even practicing sitting mediation as you do, but still I’m not able to

get hold of it.”

“There! Now it’s pacified!”

[Huike – Zen Masters of China: 48-51; The Story of Zen: 133-35]